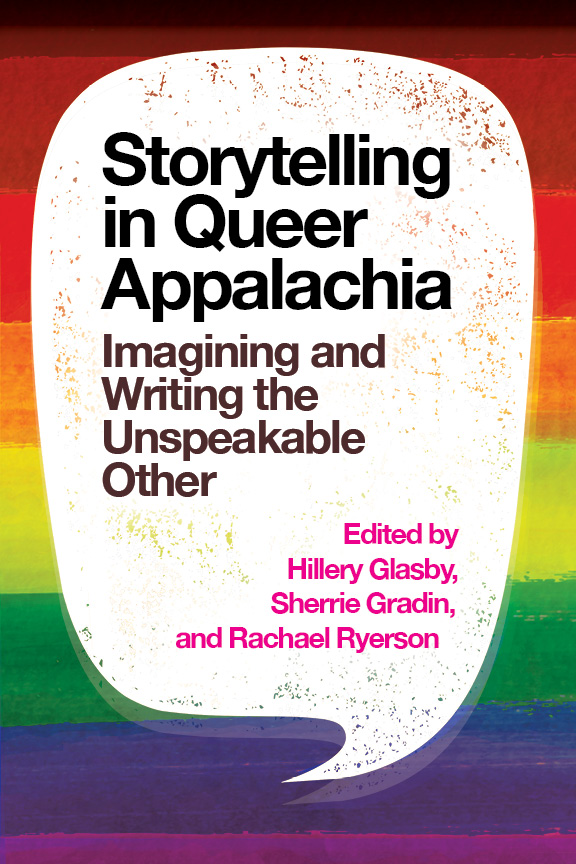

Storytelling in Queer Appalachia: An Interview with Hillery Glasby, Sherrie Gradin, and Rachael Ryerson

By ERIKA KITZMILLER

What inspired you to write this book?

The University of West Virginia Press contacted us because they are interested in publishing alternative voices from Appalachia. As queer scholars who were living in Appalachia, we thought it would be a great idea to edit a collection of narratives that blend story and scholarship through the experiences of Appalachian queer writers. Appalachia is diverse and rich in culture; and yet, rarely have Appalachians been given the space and resources to speak for themselves. When we took up this project, so little had been written about/from queer Appalachians, we felt compelled to give voice to queer Appalachia and start a wider conversation. We hope that we have accomplished both!

Can you tell me about the book? What do you hope your readers take away or learn from the book?

The book frames Appalachian queerness as a unique intersectional identity tied to place, and we hope LGBTQIA+ readers to find affinity, community, and solidarity in the book. That is, we want other queer Appalachians to feel seen and heard, and we to share nuanced versions of Appalachian queerness with audiences beyond that community so they better understand the different shades of queer Appalachian experience.

What did you learn when writing the book?

Beyond the wonderful experience of collaborating with other queer Appalachian scholars and community activists, we learned that there are so many untold and unheard stories out there about what it is like to navigate and celebrate being both Appalachian and queer–two identities that are often cast in opposition or as being unrelated.

What surprised you as you wrote this book?

What surprised us most was/is the sheer variety of queer Appalachian perspectives and experiences captured in the contributors’ pieces. The contributions in the book range from a letter to “my dear fellow Appalachians,” to a reflections on being “quare” (and academic), to experiences navigating hostile rural environments as an Appalachian queer, to analyses of queer Appalachian media/texts like zines, films, and Instagram accounts. Another surprise was that these texts share in common that they are examples of Appalachian storytelling, which isn’t all that surprising considering storytelling is endemic to rural Appalachia and queer memory/memorializing. Thus, we chose to include storytelling in the title because what readers have in our book is a collection of stories about what it means to be queer and Appalachian.

How did you pick the title? What does the title mean?

We didn’t want to separate Appalachian-ness from queerness, or Appalachian culture from queer culture because these are not mutually exclusive identities. It was important to directly name a queer Appalachian identity in the title because dominant narratives of Appalachia often exclude queer voices and queerness. We also wanted to position Appalachia as an inherently queer place–one that has always been set on the margins and outside of, and exploited by, mainstream normative culture. Finally, while many of the pieces in this book differ from one another in terms of the perspectives or experiences captured, they share in common that they are delivered through an important Appalachian tradition: storytelling.

What misconceptions about Appalachia, if any, does your book address? What do you hope people from the area learn from your work? What do you hope outsiders learn from your work?

We have touched on this in some of our other answers, but we wanted to disrupt the typical view of Appalachia as repressed, depressed, monolithic, and worthy of critique and analysis from outsiders. Also, as we say below, many queer Appalachians have suffered and struggled to be authentic and valued in their communities, but queer people in Appalachia are also survivors, fighters, integral members of their communities, sometimes full of joy in spite of difficult circumstances, and without doubt, fabulous storytellers and cultural critics. We hope outsiders learn that Appalachia is a vibrant, multifaceted place that has active social justice activists, and that queer people of all kinds live, love, write, and thrive in spite of the many geographic caricatures of place and the battle for acceptance.

What is about Appalachia that makes you proud? Or that motivated you to write about it?

Appalachia has a robust and inspiring history of activists, from the Battle at Blair Mountain to current resistance movements against the Mountain Valley Pipeline. Appalachians are survivors, thrivers, and fighters for their rights. They fight for the land and deeply value their connection to it.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Two things: the book focuses on the tensions and suffering of navigating being both queer and

Appalachian but it also celebrates those identities. There are so many individuals and groups, like STAY (Stay Together Appalachian Youth), that are focused on building queer Appalachian joy and pride within Appalachia, and we don’t want those narratives to go unnoticed. We also want to acknowledge and lift up stories of Appalachians that share other unseen identities as well: Affrilachians, transnational Appalachians, Indian Appalachians and so on. More people need to support, engage, and seek these stories (like Neema Avashia’s Another Appalachia: Coming Up Queer and Indian in a Mountain Place and William H Turner’s Harlan Renaissance: Stories of Black Life in Appalachian Coal Towns) so they gain traction as Appalachian identities and stories continue to proliferate.